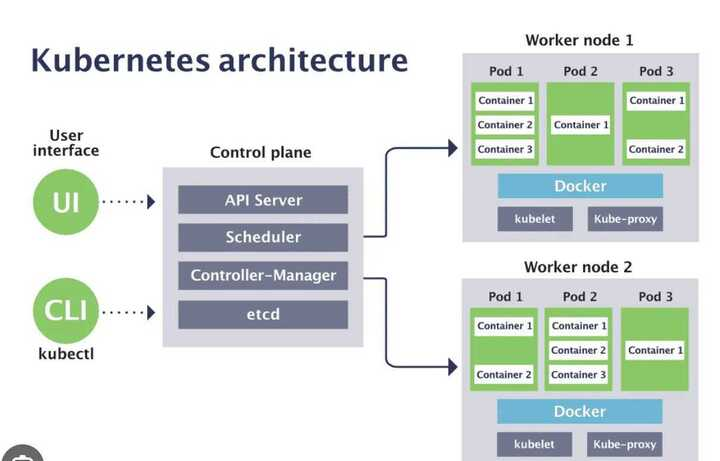

Kubernetes is two things

- A cluster for running applications

- An orchestrator of cloud-native microservices apps

Kubernetes cluster

A Kubernetes cluster contains six main components:

API server:Exposes a REST interface to all Kubernetes resources. Serves as the front end of the Kubernetes control plane.Scheduler: Places containers according to resource requirements and metrics. Makes note of Pods with no assigned node, and selects nodes for them to run on.Controller manager: Runs controller processes and reconciles the cluster’s actual state with its desired specifications. Manages controllers such as node controllers, endpoints controllers,replica,statefulset,cron and replication controllers.Kubelet: Ensures that containers are running in a Pod by interacting with the Docker engine , the default program for creating and managing containers. Takes a set of provided PodSpecs and ensures that their corresponding containers are fully operational.Kube-proxy: Manages network connectivity and maintains network rules across nodes. Implements the Kubernetes Service concept across every node in a given cluster.Etcd:Stores all cluster data like how many pod and there replica count . Consistent and highly available Kubernetes backing store. all yaml file and current pod status are stored here

Ways to create kubernetes cluster

- Kind [Fast and easy]

- Minikube

- microk8s

- kudeadm

- Google cloud platform

- AWS

- Azure

Nodes

Nodes are the workers of a Kubernetes cluster. At a high-level they do three things:

- Watch the API Server for new work assignments

- Execute new work assignments

- Report back to the control plane (via the API server)

Nodes contain

-

Kubelet →When you join a new node to a cluster, the process installs kubelet onto the node. The kubelet is then responsible for registering the node with the cluster. Registration effectively pools the node’s CPU, memory, and storage into the wider cluster pool. One of the main jobs of the kubelet is to watch the API server for new work assignments. Any time it sees one, it executes the task and maintains a reporting channel back to the control plane.

-

Container runtime →The Kubelet needs a container runtime to perform container-related tasks things like pulling images and starting and stopping containers.There are lots of container runtimes available for Kubernetes. One popular example is cri-containerd .

-

Kube-proxy →This runs on every node in the cluster and is responsible for local cluster networking. For example, it makes sure each node gets its own unique IP address, and implements local IPTABLES or IPVS rules to handle routing and load-balancing of traffic on the Pod network.

Resources mangement

When the node is running out of the resources for the pod. it will kill the pod that does not have resources mentioned in deployment file.

Pods (it’s just a sandbox for hosting containers.)

The simplest model is to run a single container per Pod. However, there are advanced use-cases that run multiple containers inside a single Pod. An infrastructure-centric use-case for multi-container Pods is a service mesh.

Pod lifecycle

Pods are mortal. They’re created, they live, and they die. If they die unexpectedly, you don’t bring them back to life. Instead, Kubernetes starts a new one in its place

How do we deploy Pods

To deploy a Pod to a Kubernetes cluster you define it in a manifest file and POST that manifest file to the API Server. The control panel verifies the configuration of the YAML file, writes it to the cluster store as a record of intent, and the scheduler deploys it to a healthy node with enough available resources. This process is identical for single-container Pods and multi-container Pods.

We can also run the Pod directly mention the docker image kubctl run podName --image=nignix:alpline

Pods and cgroups

At a high level, Control Groups (cgroups) are a Linux kernel technology that prevents individual containers from consuming all of the available CPU, RAM and IOPS on a node. You could say that cgroups actively police resource usage.Individual containers have their own cgroup limits.

Pod manifest files

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: hello-pod

labels:

zone: prod

version: v1

spec:

containers:

- name: hello-ctr

image: nigelpoulton/k8sbook:latest

ports:

- containerPort: 8080-

The .apiVersion field tells you two things – the API group and the API version.

-

.kind field tells Kubernetes the type of object is being deployed.

-

.metadata section is where you attach a name and labels These help you identify the object in the cluster, as well as create loose couplings between different objects. You can also define the Namespace that an object should be deployed to. Keeping things brief,

Namespaces are a way to logically divide a cluster into multiple virtual clusters for management purposes.In the real world, it’s highly recommended to use namespaces, however, you should not think of them as strong security boundaries. -

The .spec section is where you define the containers that will run in the Pod.

-

kubectl apply -f pod.yml→command to POST the manifest to the API server. -

kubectl get pods→command to check the status. -

kubectl get pods hello-pod -o yaml→ To get more details about pod -

kubectl describe pods hello-pod→This provides a nicely formatted multi-line overview of an object. It even includes some important object lifecycle events. -

kubectlexec -it hello-pod --sh→command will log-in to the first container

Pod Auto Scalling

Types

- Cluster (add more nodes when then cluster is full)

- Horizontal pod autoscale (scale up pod up and down based on metrics)

- Vertical pod autoscale (increase the resoures limit tool avalible for vertical pod autoscaler)

- keda (event driven autoscalling)

Horizontal Pod Autoscaling (HPA):

apiVersion: autoscaling/v2beta2

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: my-app-hpa

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: my-app-deployment

minReplicas: 2

maxReplicas: 10

metrics:

- type: Resource

resource:

name: cpu

targetAverageUtilization: 50

# this will scale the pod based on no of request

metrics:

- type: Pods

pods:

metric:

name: http_requests

target:

type: AverageValue

averageValue: 1000ReplicaSet

To deploy multiple instance. A ReplicaSet is defined with fields, including a selector that specifies how to identify Pods it can acquire, a number of replicas indicating how many Pods it should be maintaining, and a pod template specifying the data of new Pods it should create to meet the number of replicas criteria. A ReplicaSet then fulfills its purpose by creating and deleting Pods as needed to reach the desired number. When a ReplicaSet needs to create new Pods, it uses its Pod template.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: ReplicaSet

metadata:

name: frontend

labels:

app: guestbook

tier: frontend

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

tier: frontend

template:

metadata:

labels:

tier: frontend

spec:

containers:

- name: php-redis

image: gcr.io/google_samples/gb-frontend:v3Deployments vs ReplicaSet

Deployment is a higher-level concept that manages ReplicaSets and provides declarative updates to Pods along with a lot of other useful features. Therefore, we recommend using Deployments instead of directly using ReplicaSets

CMD

kubectl get rs→ get all replica

Deployments

Deploy Pods indirectly via a higher-level controller. Examples of higher-level controllers include; Deployments, DaemonSets, and StatefulSets.

For example, a Deployment is a higher-level Kubernetes object that wraps around a particular Pod and adds features such as scaling, zero-downtime updates, and versioned rollbacks.

Behind the scenes, Deployments, DaemonSets and StatefulSets implement a controller and a watch loop that is constantly observing the cluster making sure that current state matches desired state.

Depolyment strategies

to manage the rollout and updates of applications within a cluster. These strategies help in achieving continuous delivery, minimizing downtime, and ensuring reliability.

Rolling Update Deployment (default)

- This strategy gradually replaces old pods with new ones, ensuring that there is always a specified number of replicas available.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: example-deployment

spec:

replicas: 3

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxUnavailable: 1

maxSurge: 1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: example

spec:

containers:

- name: example-container

image: example:new-version

- maxUnavailable → maximum number or percentage of pods that can be unavailable during the update

- maxSurge → maximum number or percentage of pods that can be created above the desired replica count during the update

Recreate Deployment:

- In this strategy, the existing pods are terminated all at once, and new pods with the updated version are created.

- have down time (used on dev )

Blue-Green Deployment:

- there are two separate environments (blue and green), and the traffic is switched between them after a successful update.

Canary Deployment:

- deployment introduces the new version of the application to a subset of users or traffic.

Difference between pod and Deployments

Pods don’t self-heal, they don’t scale, and they don’t allow for easy updates or rollbacks. Deployments do all of these. As a result, you’ll almost always deploy Pods via a Deployment controller.

Desired state is what you want. Current state is what you have. If the two match, everybody’s happy.

The declarative model is a way of telling Kubernetes what your desired state is, without having to get into the detail of how to implement it. You leave the how up to Kubernetes.

Reconciliation loops

Fundamental to desired state is the concept of background reconciliation loops (a.k.a. control loops). For example, ReplicaSets implement a background reconciliation loop that is constantly checking whether the right number of Pod replicas are present on the cluster. If there aren’t enough, it adds more. If there are too many, it terminates some. To be crystal clear, Kubernetes is constantly making sure that current state matches desired state.

Rolling updates with Deployments

Now, assume you’ve experienced a bug, and you need to deploy an updated image that implements a fix. To do this, you update the same Deployment YAML file with the new image version and re-POST it to the API server. This registers a new desired state on the cluster, requesting the same number of Pods, but all running the new version of the image. To make this happen, Kubernetes creates a new ReplicaSet for the Pods with the new image.You now have two ReplicaSets – the original one for the Pods with the old version of the image, and a new one for the Pods with the updated version. Each time Kubernetes increases the number of Pods in the new ReplicaSet (with the new version of the image) it decreases the number of Pods in the old ReplicaSet (with the old versionof the image). Net result, you get a smooth rolling update with zero downtime.

Deployments manifest files

apiVersion: apps/v1 #Older versions of k8s use apps/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: hello-deploy

spec:

replicas: 10

selector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

minReadySeconds: 10

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxUnavailable: 1

maxSurge: 1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

spec:

containers:

- name: hello-pod

image: nigelpoulton/k8sbook:latest

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

resources:

request: (A minimum value)

cpu : 1m

memory: 1024Mi (in MB)

limit: (A maxx value can be used)

cpu: 3m

memory: -

The .specsection is where most of the action happens. Anything directly below .spec relates to the Pod. Anything nested below -

.spec.templaterelates to the Pod template that the Deployment will manage. In this example, the Pod template defines a single container. -

.spec.replicastells Kubernetes how may Pod replicas to deploy -

.spec.selectoris a list of labels that Pods must have in order for the Deployment to manage them. -

.spec.strategytells Kubernetes how to perform updatesto the Pods managed by the Deployment.Update using the RollingUpdate strategy- Never have more than one Pod below desired state ( maxUnavailable: 1 )

- Never have more than one Pod above desired state ( maxSurge: 1 )

-

.spec.minReadySecondsThis is set to 10 , telling Kubernetes to wait for 10 seconds between each Pod being updated.(on new deployment) -

resourcesto allocate the min and max resources need for the Pod before make sure that node have enough resources to allocate it bykubctl describe node -

if we not specifiy the resources it take full node resources as it needed.

-

kubectl apply -f deploy.yml→ will send the yml to API server to deploy -

kubectl get deploy hello-deploy

Affinity and Anti-Affinity

Affinity and Anti-Affinity are concepts used to control how pods are scheduled on to nodes in a cluster. They help define rules for pod placement based on characteristics of the nodes or other pods in the cluster.

Affinity: Affinity rules specify conditions that pods prefer for their placement. Pods with affinity rules tend to be scheduled onto nodes that meet those conditions

Anti-Affinity: Anti-affinity rules, on the other hand, specify conditions that pods should avoid for their placement. Pods with anti-affinity rules tend to be scheduled away from nodes or pods that meet those conditions

It is use full when we need high avaliblity of the server in different node

Yaml file explained

API Version

specifies the version of the Kubernetes API that should be used for the resource described in that file.The format of the apiVersion field is typically <group>/<version>

Type of groups

- Core API Group (

v1): Resources likePod,Service,Namespace,PersistentVolume,PersistentVolumeClaim, etc. useapiVersion: v1 - Apps API Group (

apps/v1,apps/v1beta1,apps/v1beta2): for managing higher-level abstractions of applications and workloads, includingDeployment,StatefulSet,ReplicaSet, andDaemonSet. - Batch API Group (

batch/v1,batch/v1beta1): related to batch processing, such asJobandCronJob. - Networking API Group (

networking.k8s.io/v1,networking.k8s.io/v1beta1): related to networking, includingNetworkPolicy.

Kind

The type of resource being defined.

- Pod:

- Represents a single instance of a running process in a cluster.

- Service:

- Defines a set of Pods and a policy to access them as a network service.

- ReplicationController:

- Ensures a specified number of replicas for a set of Pods. Deprecated in favor of Deployments and ReplicaSets.

- Deployment:

- Declaratively manages a desired state for Pods and ReplicaSets.

- StatefulSet:

- Manages the deployment and scaling of a set of Pods with unique identities.

- DaemonSet:

- Ensures that a specified Pod runs on each node in the cluster.

- ReplicaSet:

- Ensures a specified number of replicas for a set of Pods. Often used by Deployments.

- Job:

- Creates one or more Pods and ensures they run to completion.

- CronJob:

- Creates Jobs on a schedule specified by a cron expression.

- Namespace:

- Provides a way to divide cluster resources into multiple virtual clusters.

- ConfigMap:

- Holds configuration data as key-value pairs for Pods to consume.

- Secret:

- Stores sensitive information, such as passwords or API keys, as key-value pairs.

- Ingress:

- Manages external access to services in a cluster, typically HTTP.

- NetworkPolicy:

- Specifies how groups of Pods are allowed to communicate with each other and other network endpoints.

- ServiceAccount:

- Provides an identity for processes that run in a Pod.

- PersistentVolume:

- Represents a piece of networked storage in the cluster that can be mounted into a Pod.

- PersistentVolumeClaim:

- Requests a specific amount of storage from a PersistentVolume.

- Role and RoleBinding:

- Define access controls within a namespace.

- ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding:

- Define access controls across the entire cluster.

- HorizontalPodAutoscaler:

- Automatically adjusts the number of Pods in a deployment or replica set.

Metadata

used to provide data about the resource itself

nameSpecifies a name for the resource. The name must be unique within its namespace for most resource types.namespacethe namespace in which the resource should be created.labelsmap of key-value pairs that can be used to organize and categorize resources

Spec

is used to define the desired state of the resource. The spec section contains the configuration parameters and settings that specify how the resource should behave. The structure of the spec field varies depending on the type of resource being defined, as each resource type has its own set of properties and specifications.

Example

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: test-certbot

namespace: nginx-ingress

labels:

app: certbot

environment: test

spec:

replicas: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: certbot

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: certbot

environment: test

spec:

securityContext:

fsGroup: 1000

runAsUser: 1000

containers:

- name: certbot

image: test-certbot:latest

command: ["node"]

args: ["server.js"]

- Kuberentes apply from bottom first it will create a 2 pod with label certbot

- Then replica will be created to monitor the pod status does is have 2 active pod by using selector

- Then depolyment will be created

What happend when we apply yml file

when we run kubctl apply -f name.yml

- The

kubectlcommand communicates with the Kubernetes API server.The API server performs several tasks, including authentication, authorization, validation, and admission control. Once the YAML file has passed validation and admission control, the API server persists the resource information in etcd. - Controllers in Kubernetes operate on a watch loop. They continuously watch for changes in the desired state of resources by querying etcd for updates.When a new resource is stored in etcd, controllers that are responsible for that resource type are notified.

- Based on the reconciled desired state, controllers initiate actions to bring the cluster to the desired state. In the case of a Deployment, this may involve creating new Pods to meet the specified replica count.

- Controller store the Pod object to etcd then the Scheduler is responsible for assigning Pods to available nodes in the cluster.It selects an appropriate node based on factors such as available resources, node affinity/anti-affinity rules, and other constraints specified in the Pod’s configuration

- Next Kubelet get notified for actually creating and managing the containers within Pods

- Once Kubelet run the pod sucessfully it update the status on etcd.

Probe

- Liveness Probe indicates if the container is operating. If so, no action is taken. If not, the kubelet kills and restarts the container. Liveness probes are used to tell kubernetes to restart a container. If the liveness probe fails, the application will restart. This can be used to catch issues such as a deadlock and make your application more available.

- Readiness Probe indicates whether the application running in the container is ready to accept requests. If so, Services matching the pod are allowed to send traffic to it. If not, the endpoints controller removes the pod from all matching Kubernetes Services.

Note:If you don’t set the readiness probe, the kubelet assumes that the app is ready to receive traffic as soon as the container starts. If the container takes 2 minutes to start, all the requests to it will fail for those 2 minutes. - Startup Probe indicates whether the application running in the container has started. If so, other probes start functioning. If not, the kubelet kills and restarts the container.

readinessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /ready

port: 80

httpHeaders:

name: X-Custom-Header

value: "CustomValue"

#we can give as exec like below

livenessProbe:

exec:

command:

- sh

- -c

- "nc -z localhost 5432 || exit 1"Services

When newly pods created are scaled it will have new IP so if we have other pod communicating with it. it is unrealible.This is where Services come in to play. Services provide reliable networking for a set of Pods.

They operate at the TCP and UDP layer, Services do not possess application intelligence and cannot provide application-layer host and path routing.for that we use ingress

Services use labels and a label selector to know which set of Pods to load-balance traffic to.

kube-proxy is responsible for all assign the IP , forwarding packet, load balancing etc.

proxy_pass http://SERVICE-NAME.YOUR-NAMESPACE.svc.cluster.local:8080;can be accessed

Kube Proxy

installed on every node and runs in our cluster in the form of a DaemonSet.

How it works

After Kube-proxy is installed, it authenticates with the API server. When new Services or endpoints are added or removed, the API server communicates these changes to the Kube-Proxy.

Kube-Proxy then applies these changes as NAT rules inside the node. These NAT rules are simply mappings of Service IP to Pod IP. When a request is sent to a Service, it is redirected to a backend Pod based on these rules.

Now let’s get into more details with an example.

Assume we have a Service SVC01 of type ClusterIP. When this Service is created, the API server will check which Pods to be associated with this Service. So, it will look for Pods with labels that match the Service’s label selector.

Let’s call these Pod01 and Pod02. Now the API server will create an abstraction called an endpoint. Each endpoint represents the IP of one of the Pods. SVC01 is now tied to 2 endpoints that correspond to our Pods. Let’s call these EP01 and EP02.

Now the API server maps the IP address of SVC01 to 2 IP addresses, EP01 and EP0 and API server advertises the new mapping to the Kube-proxy on each node, which then applies it as an internal rule.

Kube-Proxy can operate in three different modes, user-space mode, IPtables mode, and IPVS mode.

- user-space mode not used now IPtables and IPVS are used now where iptables are timeconsuming compared to IPVS to lookup o(n)

By default, Kube-proxy runs on port 10249 and exposes a set of endpoints that you can use to query Kube-proxy for information.

we can use the /proxyMode endpoint to check the kube-proxy mode.

Types

ClusterIP (default)

- has a stable IP address and port that is only accessible from inside the cluster

- It will get registered in kube DNS and when every Pod IP change kube will take care of it so we can just use the service name to communicate

Service YAML

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: hello-svc #Name registered with cluster DNS

spec:

ports:

- port: 8080 #the port the service need to be listen

targetPort: 8080 # the port the app is running

selector:

app: hello-world

# Label selector

# Service is looking for Pods with the label `app=hello-world` can be any key and vaule

deploy.yml

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: hello-deploy

spec:

replicas: 10

selector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

# Pod labels

# The label matches the Service's label selector

spec:

containers:

- name: hello-ctr-

the Service has a label selector (

.spec.selector) with a single value app=hello-world This is the label that the Service is looking for when it queries the cluster for matching Pods. -

The Deployment specifies a Pod template with the same app=hello-world label (

.spec.template.metadata.labels) -

the Service will select all 10 Pod replicas and provide them with a stable networking endpoint and load-balance traffic to them.

-

kubectl get services→ Will list all service with IP get the IP from here -

To connect with service user the service name or ip by

kubectl get services -

Redis(host="servicename",port="8080")in code level to acess the Pod

Headless service:

- Sometimes you don’t need load-balancing and a single Service IP. In this case, you can create what are termed headless Services, by explicitly specifying

"None"for the cluster IP address - This also help us if we want to pod to pod communication NodePort service:

- This builds on top of ClusterIP and enables access from outside of the cluster (static ip). Port range can be only between 30000 to 32767

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: my-service

spec:

type: NodePort

selector:

app.kubernetes.io/name: MyApp

ports:

- port: 80

# By default and for convenience, the `targetPort` is set to

# the same value as the `port` field.

targetPort: 80

# Optional field

# By default and for convenience, the Kubernetes control plane

# will allocate a port from a range (default: 30000-32767)

nodePort: 30007Loadbalancer Service

- On cloud providers which support external load balancers, setting the

typefield toLoadBalancerprovisions a load balancer for your Service. example ingress

Ingress

An Ingress is an API object that provides HTTP and HTTPS routing to services based on rules defined by the user.

-

Ingress as Deployment: Refers to deploying the Ingress controller as a set of pods using a Deployment resource.

-

Ingress as kind Ingress: Refers to using the Ingress resource itself to define routing rules for incoming traffic.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: example-ingress

spec:

rules:

- host: myapp.example.com #like ngnix it will accept only the request came form the domain

http:

paths:

- path: /app

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: myapp-service

port:

number: 80

Ingress Controller is a component responsible for implementing the rules defined in the Ingress resource. It watches for changes to Ingress resources and configures the underlying load balancer or reverse proxy to handle incoming requests accordingly. Popular Ingress Controllers include NGINX Ingress Controller, Traefik, and HAProxy Ingress

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: nginx-ingress-controller

namespace: ingress-nginx

spec:

replicas: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nginx-ingress

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: nginx-ingress

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx-ingress

image: 'nginx/nginx-ingress:latest'

ports:

- name: http

containerPort: 80

- name: https

containerPort: 443

Service → To expose the ingress controller

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: nginx-ingress

namespace: ingress-nginx

spec:

type: LoadBalancer

ports:

- name: http

port: 80

targetPort: http

- name: https

port: 443

targetPort: https

selector:

app: nginx-ingress

Endpoint Objects

Kubernetes is constantly evaluating the Service’s label selector against the current list of healthy Pods on the cluster. Any new Pods that match the selector get added to the Endpoints object, and any Pods that disappear get removed. This means the Endpoints object is always up to date. Then, when a Service is sending traffic to Pods, it queries its Endpoints object for the latest list of healthy matching Pods. Every Service gets its own Endpoints object with the same name as the Service.This object holds a list of all the Pods the Service matches and is dynamically updated as matching Pods come and go.

CMD

kubectl get pod -o wide→ will display the IPkubectl apply -f svc.yml→Tells Kubernetes to deploy a new object from a file called svc.yml . The .kind field in the YAML file tells Kubernetes that you’re deploying a new Service object.kubectl get svc hello-svc→Introspecting Services display the IPkubectl get ep hello-svc→the Endpoint controller’s

Kubernetes DNS

Every Pod on the cluster, meaning all containers and Pods know how to find it. Every new service is automatically registered with the cluster’s DNS so that all components in the cluster can find every Service by name. Some other components that are registered with the cluster DNS are StatefulSets and the individual Pods that a StatefulSet manages.Cluster DNS is based on CoreDNS (https://coredns.io/).

Network policies

By default all pod can communicate with other even in different namespace just by knowing the IP. If we want restrict that use network policies

Networking

When we create a Kubernetes Service, it gets assigned a Cluster IP (also known as a virtual IP). This Cluster IP is managed by iptables on each node in the cluster.

Here’s how iptables is typically used in Kubernetes for routing traffic to different pods:

- Service Cluster IP Routing:

- When you create a Service in Kubernetes, it gets assigned a Cluster IP, which is an internal IP address.

- iptables rules are automatically configured on each node in the cluster to forward traffic destined to the Service’s Cluster IP to one of the Service’s endpoints (Pods).

- These iptables rules typically reside in the

nattable and are managed by kube-proxy, which runs on each node in the cluster. - kube-proxy watches the Kubernetes API server for changes to Services and Endpoints, and it updates iptables rules accordingly to ensure that traffic is properly routed to the appropriate Pods.

- Service External Traffic Routing:

- In addition to routing internal traffic within the cluster, iptables can also be used to route external traffic to Services.

- When you expose a Service externally (e.g., using a NodePort, LoadBalancer, or Ingress), iptables rules are configured to forward external traffic to the appropriate Service Cluster IP.

- Pod-to-Pod Communication:

- iptables rules are also used for enabling communication between different Pods in the cluster.

- Kubernetes assigns a unique IP address to each Pod, and iptables rules are configured to allow communication between Pods within the same namespace or across namespaces if Network Policies allow.

- Network Policies:

- Network Policies in Kubernetes allow you to define rules for controlling traffic to and from Pods.

- iptables rules are used to enforce these Network Policies, allowing or blocking traffic based on the defined rules.

IPTable

iptables -t nat -L -n →displays the current NAT (Network Address Translation) table rules the output contain

- Chain (Chain name):

- Each line starts with the chain name, which indicates the specific chain within the NAT table where the rule is applied. Common chains include

PREROUTING,POSTROUTING, andOUTPUT. PREROUTING→ apply the rule before routing,POSTROUTING→ after routing andOUTPUTis for when the packets send to externam

- Each line starts with the chain name, which indicates the specific chain within the NAT table where the rule is applied. Common chains include

- num:

- The

numcolumn displays the sequential number of the rule within the chain. This number is used for referencing and managing rules.

- The

- target:

- The

targetcolumn indicates the target action to be taken when a packet matches the rule. Common targets includeDNAT,SNAT,MASQUERADE,REDIRECT, etc. DNAT (Destination Network Address Translation)is used to rewrite the destination IP address and/or port of packets as they pass through the firewall.SNATis used to rewrite the source IP address and/or port of packets as they pass through the firewallMASQUERADEis a special case of SNAT and is commonly used when the outbound interface’s IP address is dynamically assigned (e.g., using DHCP).REDIRECTis used to redirect packets to the local machine itself, typically to a different port on the same machine.

- The

- prot:

- The

protcolumn specifies the protocol (e.g., tcp, udp) for which the rule is defined.

- The

- source:

- The

sourcecolumn specifies the source IP address or IP range from which packets are matched against the rule.

- The

- destination:

- The

destinationcolumn specifies the destination IP address or IP range to which packets are matched against the rule.

- The

- options:

- The

optionscolumn provides additional options or flags associated with the rule. This may include port numbers, interface names, etc.

- The

- Original and Translated IP addresses/ports:

- For DNAT and SNAT rules, you may see columns indicating the original and translated IP addresses or ports. These columns show the transformation that occurs on the packet’s source or destination IP address or port.

Note: use ip command

Kubernetes storage

When we restart the pod the data stored in pod will go. To solve this we using Kubernetes storage

Storage for single pod

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: local-web

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: local-web

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: local-web

spec:

containers:

- name: local-web

image: nginx

ports:

- name: web

containerPort: 80

volumeMounts:

- name: local -> label must need to match with voulme

mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html #Path inside the container

volumes:

- name: local

hostPath:

path: /var/nginxserver- When we store data in

/usr/share/nginx/htmlin this dir it will be stored in/var/nginxserverthis kind of storage cannot be shared among the pod and nodes

Shared storage

The three main resources in the persistent volume subsystem are:

- Persistent Volumes (PV)

- Storage Classes (SC) → Type of storage class ex NFS,AWS,azure..etc

- Persistent Volume Claims (PVC) → used to claim the storage that was alloacted using PV

-

First create PV with following

apiVersion: v1 kind: PersistentVolume metadata: name: nfs spec: capacity: storage: 500Mi persistentVolumeReclaimPolicy: Retain accessModes: - ReadWriteMany storageClassName: nfs #type of storage that we using nfs: server: 192.168.1.7 path: "/srv/nfs".spec.accessModesdefines how the PV can be mounted. Three options exist:- ReadWriteOnce (RWO)

- ReadWriteMany (RWM)

- ReadOnlyMany(ROM)

- ReadWriteOnce defines a PV that can only be mounted/bound as R/W by a single PVC. Attempts from multiple PVCs to bind (claim) it will fail.

- ReadWriteMany defines a PV that can be bound as R/W by multiple PVCs. This mode is usually only supported by file and object storage such as NFS. Block storage usually only supports RWO .

- ReadOnlyMany defines a PV that can be bound by multiple PVCs as R/O. A couple of things are worth noting. First up, a PV can only be opened

persistentVolumeReclaimPolicyThis tells Kubernetes what to do with a PV when its PVC has been released. Two policies currently exist:- Delete →This policy deletes the PV and associated storage resource on the external storage system

- Retain

-

Deploy the PV by

kubctl -f apply filename.yml- kubctl get pv : to get all PV

- PV are not bound to namespace it can be accesed by any namspace

-

Create PVC to claim the pV

apiVersion: v1 kind: PersistentVolumeClaim metadata: name: mycustomvolume spec: accessModes: - ReadWriteMany storageClassName: nfs #we can create custom storage class resources: requests: storage: 100Mi4.specsection must match with the PV you are binding it with. In this example, access modes, storage class, and capacity must match with the PV. but the storage can be less then what we give inPV- It bound to namespace

kubctl describe pvc→ to describe what’ going on helpfull to debug.

-

Use it in deployment

apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: Deployment metadata: name: nfs-web spec: replicas: 1 selector: matchLabels: app: nfs-web template: metadata: labels: app: nfs-web spec: containers: - name: nfs-web image: nginx ports: - name: web containerPort: 80 volumeMounts: - name: nfs mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html volumes: - name: mycustomvolume #Label need to match persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: nfs

Config Maps

Kubernetes provides an object called a ConfigMap (CM) that lets you store configuration data outside of a Pod. It also lets you dynamically inject the data into a Pod at run-time. ConfigMaps are a map of key/value pairs and we call each key/value pair an entry.

Example

#multimap.yml

kind: ConfigMap

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: multimap

data:

DB_URL: "" # this can be acessed as var

.env : | # these content stored in file name called .env on pod

env = plex-test

endpoint = 0.0.0.0:31001

char = utf8

vault = PLEX/test

log-size = 512Mkubectl apply -f multimap.yml- Use Pipe (|) to create a as .env file

Injecting ConfigMap data into Pods and containers

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: dapi-test-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: test-container

image: registry.k8s.io/busybox

command: [ "/bin/sh", "-c", "env" ]

env:

# Define the environment variable

- name: SPECIAL_LEVEL_KEY

valueFrom:

configMapKeyRef:

# The ConfigMap containing the value you want to assign to SPECIAL_LEVEL_KEY

name: multimap

# Specify the key associated with the value

key: DB_URL

ConfigMaps and volumes

Using ConfigMaps with volumes is the most flexible option. You can reference entire configuration files as well as make updates to the ConfigMap and have them reflected in running containers.

- Create the ConfigMap

- Create a ConfigMap volume in the Pod template

- Mount the ConfigMap volume into the container

- Entries in the ConfigMap will appear in the container as individual files

Secretes

Secrets can be created independently of the Pods that use them, there is less risk of the Secret (and its data) being exposed during the workflow of creating, viewing, and editing Pods. Kubernetes, and applications that run in your cluster, can also take additional precautions with Secrets, such as avoiding writing sensitive data to nonvolatile storage.

Kubernetes Secrets are, by default, stored unencrypted in the API server’s underlying data store (etcd). Anyone with API access can retrieve or modify a Secret, and so can anyone with access to etcd. Additionally, anyone who is authorized to create a Pod in a namespace can use that access to read any Secret in that namespace; this includes indirect access such as the ability to create a Deployment.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: dotfile-secret

data:

.secret-file: dmFsdWUtMg0KDQo=

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: secret-dotfiles-pod

spec:

volumes:

- name: secret-volume

secret:

secretName: dotfile-secret

containers:

- name: dotfile-test-container

image: registry.k8s.io/busybox

command:

- ls

- "-l"

- "/etc/secret-volume"

volumeMounts:

- name: secret-volume

readOnly: true

mountPath: "/etc/secret-volume"StatefulSets

StatefulSets in Kubernetes are a resource type used to manage stateful applications, particularly those that require unique identities, stable network identifiers, and stable persistent storage. They are used for applications like databases where each instance needs a specific identity and state.

Using StatefulSets for MongoDB:

- Pod Identity: StatefulSets assign stable, predictable identities (like

mongo-0,mongo-1, etc.) to each MongoDB instance. This ensures consistency and stability crucial for proper replication and cluster coordination. - Storage: StatefulSets facilitate the use of persistent volumes, ensuring that each MongoDB instance has its dedicated and persistent storage. Even if a pod fails or needs to be rescheduled, the data remains intact and can be reattached to a new pod with the same identity.

StatefulSet Pod naming

All Pods managed by a StatefulSet get predictable and persistent names. These names are vital, and are at the core of how Pods are started, self-healed, scaled, deleted, attached to volumes, and more. The format of StatefulSet Pod names is StatefulSetName-Integer . The integer is a zero-based index ordinal, which is just a fancy way of saying “number starting from 0”

Ordered creation and deletion

StatefulSets create one Pod at a time, and always wait for previous Pods to be running and ready before creating the next. This is different from Deployments that use a ReplicaSet controller to start all Pods at the same time,causing potential race conditions.

Deleting StatefulSets

Firstly, deleting a StatefulSet does not terminate Pods in order. With this in mind, you may want to scale a StatefulSet to 0 replicas before deleting it. You can also use terminationGracePeriodSeconds to further control the way Pods are terminated. It’s common to set this to at least 10 seconds to give applications running in Pods a chance to flush local buffers and safely commit any writes that are still in-flight.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: nginx

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

ports:

- port: 80

name: web

clusterIP: None

selector:

app: nginx

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: StatefulSet

metadata:

name: web

spec:

serviceName: "nginx"

replicas: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nginx

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: registry.k8s.io/nginx-slim:0.8

ports:

- containerPort: 80

name: web

volumeMounts:

- name: www

mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html

volumeClaimTemplates:

- metadata:

name: www

spec:

accessModes: [ "ReadWriteOnce" ]

resources:

requests:

storage: 1GiMore Example refer here

Kubernetes RBAC

Kubernetes Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) allows you to define fine-grained access policies for users and services within a Kubernetes cluster.

AutoScale

Kubectl

Kubectl is the main Kubernetes command-line tool and is what you will use for your day-to-day Kubernetes management activities.

kubectl configuration file is called config and lives in $HOME/.kube . It contains definitions for: • Clusters • Users (credentials) • Contexts

Clusters is a list of clusters that kubectl knows about and is ideal if you plan on using a single workstation to manage multiple clusters. Each cluster definition has a name, certificate info, and API server endpoint.

Users let you define different users that might have different levels of permissions on each cluster. For example, you might have a dev user and an ops user, each with different permissions. Each user definition has a friendly name, a username, and a set of credentials.

Contexts bring together clusters and users under a friendly name. For example, you might have a context called deploy-prod that combines the deploy user credentials with the prod cluster definition. If you use kubectl with this context you will be POSTing commands to the API server of the prod cluster as the deploy user.

kubctl version → to get version

kube config file

apiVersion: v1

clusters:

- cluster:

certificate-authority-data: ""

server: https:/localhost:443 ## master node

name: test

contexts:

- context:

cluster: test

user: clusterUser_test_aks_rg_test

name: test

current-context: test ## Curren

kind: Config

preferences: {}

users:

- name: clusterUser_test_aks_rg_test

user:

client-certificate-data: ''

client-key-data: ''

token: ''kubectl config current-context- tell which context we are accessing currently nowkubectl config get-context→ to get all contextkubectl config use-context context-name→ to switch the context to different cluster

Namespaces

Used to isolate the resources by default it have default namespace

kubctl get namespace

kubctl -n nampace_name cmd

kubectl logs podname

kubctl exec it podname

best practices

Preventing broken connections during pod shutdown

When a request for a pod deletion is received by the API server, it first modifies the state in etcd and then notifies its watchers of the deletion. Among those watchers are the Kubelet and the Endpoints controller.the pod being removed from the iptables rules when the Endpoints controller recevie notification pod is deleted.

During any client trying to connect to it receives a Connection refused error. to solve this do following

- Graceful Termination in Application Code

- Modify the application code to handle termination signals gracefully. When a container in a pod receives a

SIGTERMsignal, it’s an indication that the pod is about to be terminated. During the shutdown process, your application should stop accepting new requests and finish processing existing ones

- Modify the application code to handle termination signals gracefully. When a container in a pod receives a

- Pre-Stop Hook

- Kubernetes supports a pre-stop hook, which is a user-defined script that is executed before a container is terminated.

- Pod Termination Grace Period

- specify a termination grace period (

terminationGracePeriodSeconds: 30) for a pod, which is the amount of time the system waits for your application to shut down gracefully. During this period, the pod remains in the “Terminating” state, allowing your application to complete any remaining work

- specify a termination grace period (

- Readiness Probes:

- can be used to prevent new requests from being directed to a pod

- Service Load Balancing:

Debugging

kubctl debug -it -n pg podname --cop-to newpodname --container containername --image imagename -- /bin/sh→ wil copy the pod and shell in to- Ephemeral container

kubctl debug -it -n pg podname

Linux namspace

- PID (process), NET,MNT(file system),Cgroup,etc all virtual file system

To see the namspace in kind

- docker ps (get the kind control node)

- docker exec -it kind-control-plane /bin/bash

- ls -l /proc/1/ns/* → print all namespace present in the process

nsenter cmd allow to excute cmd in namespace

nsenter -net=/proc/$(pgrep -o postgres)/ns/net ss --tcp -l → print all tcp connection in that namespace is same kubctl exec -it -n pg pg-postrgress -ss --tcp -l

ephemeral containers: a special type of container that runs temporarily in an existing Pod to accomplish user-initiated actions such as troubleshooting. You use ephemeral containers to inspect services rather than to build applications.

Tool

Advanced

Dynamic Admission Control for Customized Governance

Dynamic Admission Control refers to a Kubernetes feature that allows administrators to intercept, inspect, and modify requests to the Kubernetes API server before the object creation, modification, or deletion is finalized.

First create a Webhook Server: First, you’ll need a webhook server that can validate or mutate Kubernetes objects.

Register the Webhook with Kubernetes: Create ValidatingWebhookConfiguration that points to your webhook server:

apiVersion: admissionregistration.k8s.io/v1

kind: ValidatingWebhookConfiguration

metadata:

name: pod-validator-webhook

webhooks:

- name: validator.example.com

rules:

- operations:

- CREATE

apiGroups:

- ''

apiVersions:

- v1

resources:

- pods

clientConfig:

service:

name: webhook-service

namespace: default

path: /validate-pods

caBundle: <CA_BUNDLE>

admissionReviewVersions:

- v1

sideEffects: None

Helm

Helm is a package manager for Kubernetes, which helps you define, install, and upgrade applications running in a Kubernetes cluster. Helm uses charts, which are packages of pre-configured Kubernetes resources, to deploy and manage complex applications easily.

Key components of Helm include:

- Charts: Helm packages, which contain all the configuration files and templates required to set up a Kubernetes application.

- Releases: A deployed instance of a chart. Each time you install a chart into your Kubernetes cluster, it creates a release.

- Repositories: Places where charts are stored and shared.

Need to study

- job

- cronjob

- operator

Resources

- Give a idea about and overview of the architecture of that

- Design principle

- https://dev.to/leandronsp/kubernetes-101-part-i-the-fundamentals-23a1

- kubernetes 101 series

- https://github.com/jatrost/awesome-kubernetes-threat-detection

- https://openai.com/research/scaling-kubernetes-to-7500-nodes

- https://github.blog/2019-11-21-debugging-network-stalls-on-kubernetes/

- https://iximiuz.ck.page/posts/ivan-on-containers-kubernetes-and-backend-development

- https://dev.to/therubberduckiee/explaining-kubernetes-to-my-uber-driver-4f60

- kubernetes -o architecture

- https://towardsdev.com/understanding-control-pane-and-nodes-in-k8s-architecture-5572018f7624

- Demystifying container networking

- Handling Client Requests Properly with Kubernetes

- production-best-practices

- https://overcast.blog/11-kubernetes-deployment-configs-you-should-know-in-2024-1126740926f0

- Learn How To Create Network Policies for Kubernetes using GUI and interactive way

Internal Resources

- Collection of resources for inner workings of Kubernetes

- https://ronaknathani.com/blog/2020/08/how-a-kubernetes-pod-gets-an-ip-address/

- https://itnext.io/deciphering-the-kubernetes-networking-maze-navigating-load-balance-bgp-ipvs-and-beyond-7123ef428572

Products

- To cut down the cost of kubernetes

- The first cloud native service provider powered only by Kubernetes

Tools

- https://k9scli.io/ [Kubectl alternative]

- https://monokle.io/ [Monokle’s integrated open-source tools and cloud platform make it easy to define, manage, and enforce Kubernetes YAML configuration policies in minutes]

- Reloader can watch changes in

ConfigMapandSecretand do rolling upgrades on Pods - karpenter Just-in-time Nodes for Any Kubernetes Cluster

- cdk8s is an open-source software development framework for defining Kubernetes applications and reusable abstractions using familiar programming languages and rich object-oriented APIs

- Inspect all internal and external cluster communications, API transactions, and data in transit with cluster-wide monitoring of all traffic going in, out, and across containers, pods, namespaces, nodes, and clusters. https://www.kubeshark.co/

- A simple mitmproxy blueprint to intercept HTTPS traffic from app running on Kubernetes

- Always Encrypted Kubernetes

- https://github.com/k8sgpt-ai/k8sgpt is a tool for scanning your Kubernetes clusters, diagnosing, and triaging issues in simple English.

kubectl get deployments --selector=app.kubernetes.io/instance=kubesense,app.kubernetes.io/name=api -n kubesense

to get the deployment file that match the selector

network namespace are stored in /var/run/nets

Resources Mangement

The lifecycle of resource management in Kubernetes begins with defining resource requests and limits in the pod specification, which are then subjected to admission control checks by the API server to ensure adherence to resource quotas and limit ranges set by cluster administrators. Next, the Kubernetes scheduler evaluates node resources and schedules the pod to a suitable node based on its resource requests, ensuring it has sufficient allocatable resources. Finally, the kubelet on the designated node enforces resource requests and limits using Linux cgroups, controlling CPU and memory allocation, and potentially evicting pods if resource contention occurs.

While Kubernetes effectively manages resources like CPU and memory, other resources like open file descriptors, TCP connections, and process IDs (PIDs) are not directly managed by Kubernetes

- Allocating more is bad it will use other who required may not get the required resources

- vertical pod auto scaller

https://karpenter.sh/ https://github.com/kubernetes/autoscaler https://stormforge.io/pricing/

In Kubernetes, QoS classes help manage resources and ensure predictable application behavior. These classes provide a way to isolate, prioritize, and apply resource quotas to different workloads within a cluster. There are three main QoS classes in Kubernetes:

1.Guaranteed: This class offers the highest level of resource assurance. Pods in this class have their CPU and memory requests equal to their limits. Kubernetes guarantees these pods will receive the requested resources.35

2.Burstable: Pods in this class have their CPU and memory requests lower than their limits. These pods are guaranteed to receive the resources specified in their requests but can burst up to their limits if resources are available.35

3.BestEffort: Pods in this class do not specify any resource requests or limits. They run with the lowest priority and utilize leftover resources.

node reserver some cpu for himslef

-

1 CPU = 1 core.

-

1 CPU = 1,000,000 micro-CPUs (μCPU).

-

1CPU means 1 whole CPU core. -

500mCPU means 0.5 of a CPU core (500 millicores). -

restart policy

-

when pod uses more memory we allocated it will will killed but for cpu it will throtled

we have a node with 8Gb two pod with 3Gb and 2Gb using but we set request as 3 for both if new pod we put 3GB kube dont allocate eventhough it is free because it look for unscheduled memory

now if we put 6Gi and 6G for both request resour pod it will allow becuase it will look for request size

- How pod killed when memory fulled?

if ten containers are set to use one CPU each (—cpus=1) on a machine with only one CPU, they will all share that single CPU. None of the containers are guaranteed a full CPU. They each get a share of it.

Similarly, setting a memory limit doesn’t reserve a specific amount of memory. Instead, it acts as a cap, preventing the container from exceeding the defined limit.